READ

Daisy Simpson suffers from at least 30 different health conditions, but her unique needs are not met by any single NHS trust

A woman who suffers 20 strokes a week and lives with severe health anxiety is being cared for by dozens of medical teams across the UK, as her unique needs are not met by any single NHS trust.

Daisy Simpson suffers from at least 30 different health conditions, but it was the one finally diagnosed three years ago that has left her life in complete turmoil.

The 35-year-old from Brentwood, Essex, suffered a stroke and a brain bleed in January 2021. She was finally diagnosed with Moyamoya disease, which fuses the brain’s blood vessels, at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge later that year.

The disease affects just one in a million people and has left the once aspiring actress suffering around 20 strokes a week.

A shortage of life-saving medication for her severe respiratory issues has also left her extremely anxious, but it is the disjointed care she has experienced over the last decade that she believes has really hampered any chance of independent living.

“I’d normally be able to say to my carers that I feel ‘strokey’ before one happens,” she told i.

“I don’t know if the effects will be permanent or temporary. How the disease works is that some days I’ll lose my speech, which is really distressing as there are times when my carers don’t know what I need.

“I’ve got 32 different conditions and it’s so unsafe.”

Brain surgery could potentially extend Ms Simpson’s life but she would only have a 50 per cent chance of surviving the operation, according to medics. Without it, she believes she has less than five years to live.

“After I was finally diagnosed correctly, I was told it would be supportive measures and palliative care at that point.

“Then I was told my life expectancy was about five years from the first stroke, which I’m now half way through. There’s now a shortage of Reslizumab – the life-saving treatment that helps my breathing.

“I was told I wouldn’t get it until March but that’s not even certain anymore.”

Reslizumab is delivered intraveneously and essentially stops Ms Simpson from going into respiratory failure. “I’ve been told if I have an asthma attack, I’m likely to have a fatal stroke, and been left with that anxiety,” she said.

Ms Simpson usually needs intensive care treatment every four to six weeks due to her respiratory problems, which has been the case since she was 17. Her physical health has had a huge impact on her mental health.

“I’m being pumped full of drugs just to keep me alive. I’ve been under the care of multiple consultants across different trusts, but there is no one person in charge of my overall care which has been a massive problem over the years.

“I must have gone through about 12 care coordinators. It’s a real problem when they change.”

Ms Simpson had been under the care of Essex mental health services since 2006 and at one stage was diagnosed with treatment resistant schizophrenia. Her central complaint is that a lack of co-ordination across physical, mental and social services has consistently hampered her ability to maintain better health.

Essex Partnership University NHS Trust (EPUT) eventually discharged her in January this year. Her discharge letter, seen by i, states that her current health and care support needs are being met and funded by the Mid and South Essex Integrated Care Board under Continuing Health Care (CHC) – the free social care arranged and funded solely by the NHS for some people with long-term complex health needs.

It said her physical health needs and multiple complex medical conditions are being supported by “various specialists who are in liaison with your GP”.

It also said Ms Simpson is not prescribed any psychotropic medication for her mental health and has “not actively engaged and accepted the offer of support for your mental health”.

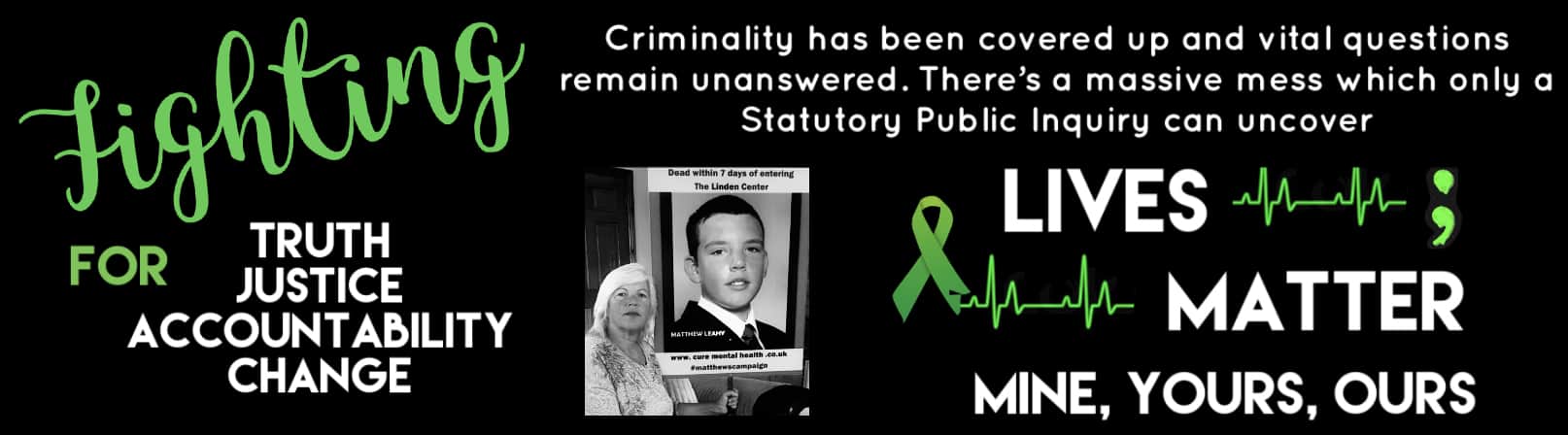

Ms Simpson argues that EPUT has “denied me my needs” and she was one of those behind the successful campaign to force the Government to move the previously independent inquiry into mental health services across Essex over a 20-year period to a statutory footing.

Her discharge letter pointed out her housing needs are being looked after by Brentwood Council, who Ms Simpson is also in dispute with now she is a full-time wheelchair user, arguing that her current house is not fit for purpose. She is taking the council to court.

“There’s not any medical professional left who knows my needs across any sector. I’ve just been left to myself. It’s quite sinister,” she said. “I only got CHC funding in 2022 after my care coordinator fought for that.

“I’m still trapped in the same house I have been in for the last few years and I’m hoping that is going to a judicial review. I lost my care funding package. No one has sorted my housing issue and, as a result, I’m likely to die more prematurely than I otherwise would.

“My mobility is worsening due to the number of strokes I have. I’m having about three a day. I can be completely paralysed, unable to sit up. I’m now getting pressure sores. It’s a dire situation but I’ve just become so matter-of-fact about it because I don’t know what else to do.

“Moyamoya is not really treatable. I could have an operation, but to have that my housing situation needs to be sorted as it’s a two-year recovery process and I’m a full-time wheelchair user. The doctors don’t think I would survive the operation anyway due to my other health issues.

“But to even be assessed to discover if the operation was viable, I’d need to have certain things sorted that my old care co-ordinator was tasked with sorting and dealing with multiple agencies. When she was removed everything stopped and I’ve been left in chaos.

“My current property just isn’t suitable. It can’t fit my medical equipment. It’s not disability compliant and hasn’t been adapted to my needs: the wheelchair doesn’t fit, the ramps are terrible.

“I have no access to my bathroom so I can maintain basic hygiene. The only thing they’ve given me is a raised toilet seat and that’s broken. It’s very depressing and is going to court now.”

Despite all her ailments, Ms Simpson had been able to live a full, independent life and to travel independently until her diagnose towards the end of 2021.

“To go from where I was to be confined to a house and a wheelchair is extremely distressing. I am bright, but I also have a brain injury, which changes things. I have a lack of blood flow to my brain, which causes me to forget what I’m saying, to repeat things. I’ll struggle to follow conversations. “

Ms Simpson claims that necessary paperwork from EPUT has not been handed over to another clinical team allowing her to focus on her end of life care.

“People with mental illness live on average 20 years shorter due to misconceptions with their physical health. These are well known things, so why is the situation I’m in being allowed to continue? I have no support worker. Should I be left to die with nothing?”

A spokesperson for Brentwood Borough Council said: “The council has specifically adapted a property for Ms Simpson’s needs, which is ready to be moved into. Ms Simpson has been invited to view the property. We have engaged with Ms Simpson’s legal representatives regarding the available adapted property.”

A spokesperson for EPUT said: “We are unable to comment on an individual’s care but continue to work with partners to ensure physical health, mental health and social care meet the needs of every patient.

“In a situation where a patient has complex health needs, teams across a number of organisations, including acute trusts, local authorities and mental health trusts work collaboratively to support people by providing the best possible support and care.”

Credit Paul Gallagher